![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

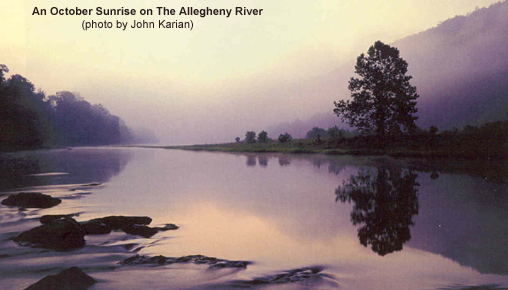

WPC has protected nearly 20,000 acres of islands, shorelines and valleys along the Allegheny River. Read more...

pH - a measurement of acidity on a scale of 0 - 14, with the number 7 representing neutrality and lower numbers indicating increasing acidity. Numbers above 7 indicate the opposite of acid, which is alkaline.

Macroinvertebrates - animals without backbones that are larger than a pencil dot. These animals live on rocks, logs, sediment, debris and aquatic plants during some period in their life. They include crayfish, mussels and snails, aquatic worms and the immature forms of aquatic insects such as stoneflies and mayflies. Most aquatic insects emerge from streams as terrestrial insects for the adult portion of their life cycle.

Erosion - The wearing away of soil by water, wind or other forces.

Sedimentation - Soil deposited on the bottom of a stream.

Riffle - A shallow area in a stream where water flows swiftly over gravel or larger stones.

Pool - An area of a stream where the water is fairly deep and flowing very slowly.

Riparian - The land adjacent to a stream or river, beginning at the stream bank and extending away from the bank into the floodplain where the land is level.

Larval fish - baby fish.

| |

Raising Our Stream Consciousness A healthy stream is like a thriving community; it provides a nice variety of living quarters for equally varied needs. Insects live in the shallow areas of streams where sunlight helps turn vegetation gathered from the stream banks into algae, a food source for this lowest level on the food chain. Baby fish, called larval fish, seek out fast flowing areas called riffles where they can attach to rocks and collect food from the flowing waters. Deep pools in the stream provide cruising spots for schools of fish. Macro-invertebrates such as aquatic insects and freshwater mussels in a healthy stream will get their nourishment from streambanks of lush forest vegetation as leaves and limbs fall into the water. The pH of a stream is a measure of how acidic the water is. Most creatures that live in water can only survive when the pH is about neutral, within a range of pH 5 to pH 7. Some cannot live in water that has any acidity. Chemicals and nutrients that enter the stream through runoff change the pH of the water. |

|

Go to the next article: Water and Agriculture: A Delicate Balance |

||