An Ordinary To-Do List for an Extraordinary House

Most homeowners can relate to peeling paint, old windows, and the endless list of home-improvement projects that are undertaken only as budgets and schedules permit. Even the world’s most famous house has a “home improvement” list – and WPC is tackling several important Fallingwater projects in 2009.

While less dramatic and costly than the extensive cantilever repair project carried out during 2002, the current items on Fallingwater’s restoration list are nonetheless critical. They include replacement of all window glass, restoration of the living room ceiling and furniture conservation.

The projects must be carried out with the meticulous care and expertise required for work performed on a house that is also a priceless work of art. The total cost is estimated to be $250,000, and members and other supporters are helping to make these projects possible through contributions.

Justin Gunther, curator of buildings and collections, said, “These projects will not only help us preserve Fallingwater, they will also protect the extensive art collection and furniture inside the house – which are an integral part of the Fallingwater experience.”

A Window of Opportunity

When Edgar Kaufmann, jr. dedicated Fallingwater to WPC in 1963, he described it as a “public resource, not a private indulgence,” and under WPC’s stewardship, Falllingwater will remain open to the public for all time. However, WPC members and Frank Lloyd Wright fans have a rare opportunity to “own” a signature component of the house – a Fallingwater window – by contributing to the house’s glass-replacement endowment.

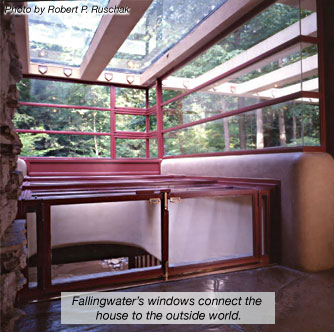

The glass in Fallingwater’s windows was last replaced in 1988, to address high UV levels that were beginning to harm its interior woodwork, furniture and art collections. Cutting-edge for the time, the project used a three-part laminated glass system in which a protective UV filter was sandwiched between 1/8-inch glass layers. Today, however, the layers have begun toseparate, causing cloudiness and reducing the windows’ ability to filter UV light. Replacing the glass – all 1,823 square feet of it – will be important not only to protect the collections inside Fallingwater, but also to restore the transparency that creates the seamless transition between the outdoors and the indoors for which Fallingwater is famous.

Once again, the glass selected for this project is a laminated system. It will maintain complete transparency and eliminate 99 percent of UV light. Installation will occur over a five-year period and involves special processes to fit the glass to Fallingwater’s unique features. For example, window glass intersects with ragged profiles of stone walls without framing. Gunther explained, “The glass runs directly into caulking channels, or chases, in the stone. This enhances the character of each material and seamlessly connects interior to exterior.”

The new window project will employ best-available technology and craftsmanship, but eventually, the windows will fail to perform optimally and will be replaced again. ’’We will be replacing the window glass every 20 years, because this is the only way to protect the wood, the art collections and the textiles in the house,” said Lynda Waggoner, director of Fallingwater and vice president of WPC.

To carry out this current project and to ensure funds will remain for future window replacements, WPC has introduced an endowment program for Fallingwater windows. In exchange for gifts that cover the cost of current and future replacements for each window, WPC is offering naming opportunities for which donors will receive a framed document that identifies a window as theirs and incorporates a sample of the old window glass. “It will be their window forever. Because these are endowed gifts, whenever we need to replace the windows, we’ll be able to do so,” said Waggoner. The price to name a Fallingwater window forever starts at $500 and goes up to $10,000. For more information, contact Carey Miller at 412-586-2356.

Preserving woodwork – painstakingly

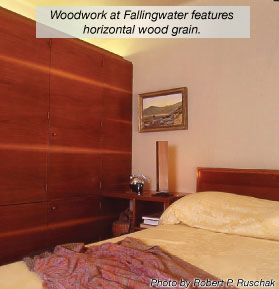

Among Fallingwater’s many remarkable details is the walnut veneer used throughout the building – on bookcases, cabinets and closet doors. The wood grain runs horizontally, echoing the horizontal lines of the house itself. Rounded edges on the shelving – called bullnose – reflect the rounded edging of concrete on the house’s parapet walls.

To ensure the woodwork could withstand the humid environment of a house built over a waterfall, Frank Lloyd Wright applied the walnut veneer to a foundation of marine-grade plywood. “Wright liked plywood at Fallingwater because it does very well in a moist setting. It will hold up better than solid timber, which may warp,” said Waggoner.

The woodwork has indeed held up well during Fallingwater’s first 73 years, but the adhesive that secures the walnut veneer to the plywood has begun to fail. “The veneer will pop off of the plywood substrate, largely because the high humidity and temperature fluctuations at Fallingwater cause the animal hide glue to deteriorate,” said Gunther.

To address this problem and other issues related to preservation of furniture and woodwork, Fallingwater staff members oversee furnitureconservation projects every year during the winter, when the house is closed. The work is done on a rotating basis so that each piece of furniture is revisited approximately every five years. “When you’re conserving furniture, anything you do should be reversible,” Gunther explained. “For this reason, we use the same adhesives and the same techniques that Frank Lloyd Wright used whenever possible.” In rare cases, he said, animal-hide glues have failed so many times that it becomes necessary to consider alternative glues, such as epoxy. “We would do this only after exhausting all other options.”

Removing paint – with a needle

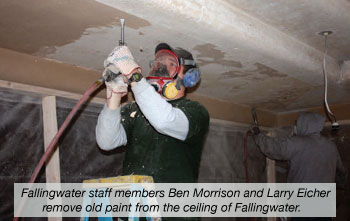

With each passing decade, Fallingwater’s walls and ceilings have been coated with layer upon layer of paint in order to protect the structure from moisture. Eventually, this measure to prevent damage became a problem unto itself. “The paint is so thick at this point, the very weight of it is pulling it off,” said Waggoner.

To address this issue, paint layers are carefully removed throughout the building, section by section, and replaced with a fresh coat of PPG paint. The benefits of this work go beyond appearance: When the paint is stripped, any structural issues – such as damage to concrete caused by rusting reinforcing steel – are revealed and can be corrected at the same time.

Addressing this problem is not a job for the impatient. Workers will use a needle-scaler, a bundle of tiny, vibrating needles that loosens paint gently, to avoid damaging walls. “We will spend two months on an area of the living room that’s 15-by-15 feet,” said Waggoner. “It’s tedious work, but it’s the best process to ensure paint is removed without damaging the building.”

2009 Members' Day and

Annual Meeting

WPC invites our members to celebrate what we’ve accomplished together. We’d also like to thank you for your loyal membership support.

The Fallingwater Cookbook

The Fallingwater Cookbook takes readers into the kitchen of Fallingwater and the world of the Kaufmanns, who entertained many famous guests at their weekend retreat.

Safeguard Your Future

For 77 years, the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy has protected this region’s land, water and wildlife. We haven’t done it alone – as a loyal member, you have played a vital part.

Become a Member

Our commitment to protect the land, water and life of Western Pennsylvania could not continue without the generous support of members like you.

Volunteer with WPC

Volunteering is an excellent way for WPC members or other concerned citizens to become actively involved. Become a volunteer today!