Bush Honeysuckle

In the warmer months of the year, many people appreciate the delicious scent of honeysuckle floating on the breeze. However, a variety of non-native honeysuckle species collectively known as bush honeysuckle (Lonicera spp.) are known to be invasive in natural areas by outcompeting important native vegetation, contributing to soil erosion, and can even be a danger to native songbirds.

- Credit: F. D. Richards, “Lonicera tartaria, 2015”, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Credit: F. D. Richards, “Lonicera tartaria, 2015”, CC BY-SA 2.0

- Credit: Melissa McMasters, “Lonicera tartaria, 2015”, CC BY-SA 2.0

Identification

The term “bush” or “shrub” honeysuckle refers to several different species of non-native invasive honeysuckle including Amur (Lonicera maackii), Morrow’s (L. morrowii), Bells (L. x bella), Standish, (L. standishii), and Tatarian (L. tatarica). Each of these species can grow to be 6-20 feet in height. Their woody stems are thornless and contain an inner hollow brown pith. Bush honeysuckle produces a plethora of shiny red berries in midsummer that are orange, red, or pink in color. Leaves are oppositely arranged on the stem and conspicuous fragrant flowers with four petals can be seen blooming in colors starting out as white and eventually turning yellow or pinkish over time. Bush honeysuckles can be found growing along roadsides, property borders, in forest openings, abandoned agricultural fields, and other disturbed locations where sunlight is prevalent.

Invasive Plant Guide: Bush Honeysuckle – Credit: Great Rivers Greenway

Bush honeysuckle may be confused with other species of native honeysuckle. The easiest way to tell the difference is to break open a stem and examine the pith. On native honeysuckles, the pith is solid, whereas non-native invasive honeysuckles have a hollow pith.

Another species of invasive honeysuckle, Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), can easily be differentiated from bush honeysuckle because Japanese honeysuckle grows as a vine whereas bush honeysuckles are woody shrubs

Additional information on how to identify bush honeysuckle can be found online.

Ecological Threat

Many species of bush honeysuckle leaf out earlier than most native plants and form dense thickets too shady for many native species to survive under. Throughout forested areas, bush honeysuckle impedes reforestation of cut or disturbed areas and prevents reestablishment of important native plants. Bush honeysuckle creates soil erosion problems because the ground beneath it becomes bare, and its open branching habit exposes songbirds’ nests to predators.

Honeysuckle Invasive Species – Credit: Iowa State University Agricultural and Natural Resources

Learn More about how to identify Bush Honeysuckle

Control and Removal

If bush honeysuckle is present on your property, please educate yourself on proper removal techniques and eliminate this plant from your property where possible. The following resources provide valuable information and tips.

How to Identify and Remove Bush Honeysuckle – Credit: Herndon Environmental Network

Other management tips can be found at:

Plant Native Alternatives

*This list is not comprehensive, but rather provides a sampling of species available for purchase from retailers located in Pennsylvania and/or surrounding states. All native plant distribution maps (below) are provided by the Biota of North America Program.

- Credit: Jim Robbins, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

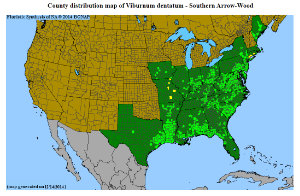

Arrowwood viburnum (Viburnum dentatum)

Arrowwood viburnum can easily be grown in average to medium moisture soils that are well-drained, and in spaces that receive full sun to part shade. Established plants have some drought tolerance.

- Credit: Melissa McMasters, “Coral honeysuckle”, CC BY 2.0

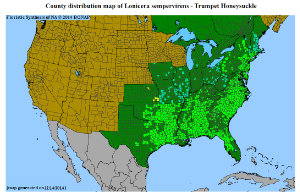

Coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens)

Coral honeysuckle is easily grown in average to medium moisture soils that are well-drained. It prefers areas that receive full sun, but can grow in spaces that are somewhat shady. Be sure to provide a support structure for this twining vine to grow on, unless you prefer it for use as a groundcover.

- Credit: peganum, “Clematis aff. viorna”, CC BY-SA 2.0

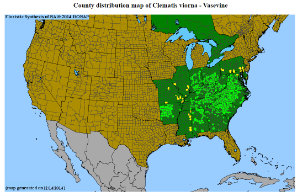

Leatherflower (Clematis viorna)

Leatherflower is a vine that prefers to grow in moist, well-drained soils and in areas that receive dappled sunlight or partial shade. Be sure to provide a support structure, such as a trellis, for it to grow on, unless you prefer it for use as a groundcover.

Learn More and Take Action

Why are Native Plants Important?

Learn more about the importance of planting native plants by reviewing the following resources. And remember, planting even one native plant on your property is a tremendous benefit to wildlife and the environment!

Doug Tallamy Explains, “Why Native Plants?”

Credit: Catherine Zimmerman

Landscaping with Native Plants in Pennsylvania

Credit: PA Department of Conservation and Natural Resources

Professor Doug Tallamy on Sustainable Landscaping

Credit: University of Delaware

Discover Native Plants.

Learn what plants are native to your area by using the National Wildlife Federation’s Native Plant Finder or the Audubon’s Native Plants Database. Both programs are easy to use - just type in your zip code and a list of native plants is provided to you.

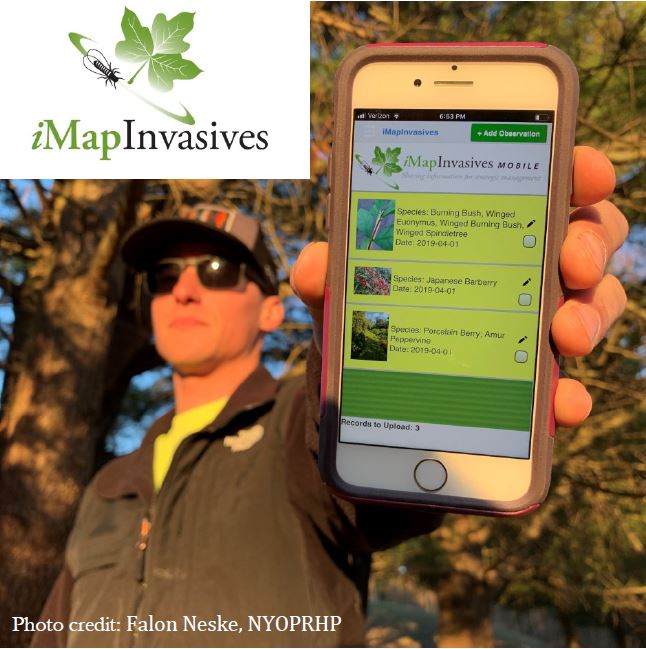

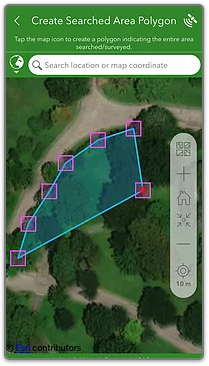

Record Invasive Species Findings with iMapInvasives.

If you find invasive plants and animals in natural areas such as parks, forests, and meadows, please report them to iMapInvasives, an online tool used by natural resource professionals and citizen scientists to record locations of invasive species The iMapInvasives program is useful in understanding species distributions statewide and is used by land managers to prioritize locations to conduct treatment efforts. In Pennsylvania, the iMapInvasives program is administered by the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy and the Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program and is financially supported by the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative. At the national level, iMapInvasives is administered by NatureServe.

A free registered user account is needed in order to contribute and view data in iMapInvasives. Register here.

How to create a presence record in iMapInvasives online (video)

Connect with Our Experts

Please direct any questions or comments regarding this species profile to Amy Jewitt, Invasive Species Coordinator, or Mary Walsh, Aquatic Zoology Coordinator.