They are charting a course for conservation and assessing rare species for possible inclusion in the 2025-2035 Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan.

Longhorn beetles, flower flies, bees, wasps, a variety of spiders, moths — in all, about 1,000 terrestrial invertebrates — are waiting in the wings for help from scientists and conservationists. Traditionally underrepresented in conservation assessments, pollinator groups and other invertebrates are undergoing assessment by Pennsylvania’s scientists for possible inclusion in Pennsylvania’s 2025-2035 Wildlife Action Plan (PA WAP).

Led by the Pennsylvania Game Commission (PGC) and Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC), the plan includes information about the distribution, habitat requirements and management needs of hundreds of PA birds, mammals, amphibians, reptiles, fish and invertebrates.

As a congressional requirement, every 10 years the PA WAP must be comprehensively reviewed and revised. This requirement provides Pennsylvania’s scientists with the opportunity to assess the status of the commonwealth’s animals and for PGC and PFBC to determine Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN). The plan also serves to guide conservation projects with the purpose to recover threatened and endangered species, prevent SGCN from requiring federal protection under the Endangered Species Act, and address species that are not rare but might be declining. Find the Species of Greatest Conservation Need list from the current (2015-2025) PA Wildlife Action Plan and more information on the Game Commission website or Fish and Boat Commission website.

Partnering with scientists and researchers at natural history museums and universities, our Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program staff are extensively assessing a long list of invertebrate species and their habitats, as well as distributions, conservation ranks, and threats to inform SGCN determinations in the 2025-2035 PA WAP.

Since completion of the 2015-2025 PA WAP, the conservation of SGCN species has been advanced through projects to assess and understand their needs. Conservation actions, including species research and habitat improvements, have been implemented through the federal State Wildlife Grant Program funding (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) through projects developed and administered by the PGC and PFBC.

Other rare species with updated information will likely be considered SCGN in the next SWAP. Read on to discover how just a few of the species have been studied and their habitat conserved, along with suggestions for how you can help conserve these species!

They are charting a course for conservation and assessing rare species for possible inclusion the 2025-2035 Pennsylvania Wildlife Action Plan.

Our Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program scientists are studying species for possible inclusion in the 2025-2035 PA Wildlife Action Plan. Here are just a few of the species they’re assessing.

Little Brown Bat

(Myotis lucifugus)

Habitat loss and white-nose syndrome have contributed to the rapid and steep population decline in bats, including the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus). PNHP zoologists and Pennsylvania Game Commission staff partnered to locate maternity roosts used by the state-endangered little brown bat at locations in Perry and Pike counties. They found some reproductive females and outfitted them with radio transmitters, with which they were able to track the bats to several roosts.

Salamander Mussels

Pollution, dams, runoff and invasive species all contribute to the sharp population decline of freshwater mussels, which quietly filter and clean our water supply. In fact, 80% of the freshwater mussel species in PA are considered Species of Greatest Conservation Need.

The state endangered salamander mussel (Simpsonaias ambigua) is a small, yellow-brown mussels known only in the Allegheny River, French Creek and Dunkard Creek. It is the only North American freshwater mussel known to use an amphibian host, the mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus). In 2022 and 2023, PNHP staff studied mudpuppy distribution in the Allegheny and Ohio rivers and evaluated the feasibility of restoring the salamander mussel to the Ohio River.

Read more about the importance, decline and study of PA’s native mussels in the PNHP 2022 Annual Report. Learn about the PFBC Salamander Mussel Species Action Plan.

Salamander Mussels

Pollution, dams, runoff and invasive species all contribute to the sharp population decline of freshwater mussels, which quietly filter and clean our water supply. In fact, 80% of the freshwater mussel species in PA are considered Species of Greatest Conservation Need.

The state endangered salamander mussel (Simpsonaias ambigua) is a small, yellow-brown mussels known only in the Allegheny River, French Creek and Dunkard Creek. It is the only North American freshwater mussel known to use an amphibian host, the mudpuppy (Necturus maculosus). In 2022 and 2023, PNHP staff studied mudpuppy distribution in the Allegheny and Ohio rivers and evaluated the feasibility of restoring the salamander mussel to the Ohio River.

Read more about the importance, decline and study of PA’s native mussels in the PNHP 2022 Annual Report. Learn about the PFBC Salamander Mussel Species Action Plan.

Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake

(Sistrurus catenatus catenatus)

In Pennsylvania, only four of 19 historic populations of the federally threatened eastern massasauga rattlesnake (Sistrurus catenatus catenatus) still exist. Population decline is due to habitat loss: Woody vegetation is shading the snakes’ preferred open field habitats and encroaches on the meadows where they are found. Indicators of environmental quality, these small, stout snakes also control rodent populations.

PNHP and agency partners from PFBC and USFWS are conducting surveys and managing their habitats. At one survey location, for example, scientists expanded massasauga habitat by removing overstory trees adjacent to high quality habitat, and then studied the snakes’ use of the newly created habitat. Soon after they emerged from hibernation, the snakes basked on the fallen trees and hunted for small mammals that share their meadow habitats. Learn about the PFBC Eastern Massasauga Species Action Plan.

Swainson’s Warbler

(Limnothlypis swainsonii)

Shy birds that often forage in the leaf litter of the forest floor, Swainson’s warblers (Limnothlypis swainsonii) are most often heard but not seen. In July 2023, WPC’s PNHP Avian Ecologist David Yeany and Bird Lab Executive Director Nick Liadis discovered the first breeding occurrence of Swainson’s warbler in Pennsylvania at Bear Run Nature Reserve—the northernmost breeding record for the species. It is presumed to be the Appalachian ecotype that prefers dense rhododendron/mountain laurel–eastern hemlock understories in mixed mature hardwood forest ravines.

Avian ecologists will continue to collaborate to create plans for its conservation and evaluation of information for the SWAP. If the Swainson’s warbler population expands its range into Pennsylvania over the long term, it could be considered an SCGN species in in the future. Data on species with shifting ranges, such as Swainson’s warbler, are useful for assessment of species for the SWAP.

Read “First Breeding Confirmation of Swainson’s Warbler in Pennsylvania” in a 2023 PNHP newsletter.

Swainson’s Warbler

(Limnothlypis swainsonii)

Shy birds that often forage in the leaf litter of the forest floor, Swainson’s warblers (Limnothlypis swainsonii) are most often heard but not seen. In July 2023, WPC’s PNHP Avian Ecologist David Yeany and Bird Lab Executive Director Nick Liadis discovered the first breeding occurrence of Swainson’s warbler in Pennsylvania at Bear Run Nature Reserve—the northernmost breeding record for the species. It is presumed to be the Appalachian ecotype that prefers dense rhododendron/mountain laurel–eastern hemlock understories in mixed mature hardwood forest ravines.

Avian ecologists will continue to collaborate to create plans for its conservation and evaluation of information for the SWAP. If the Swainson’s warbler population expands its range into Pennsylvania over the long term, it could be considered an SCGN species in in the future. Data on species with shifting ranges, such as Swainson’s warbler, are useful for assessment of species for the SWAP.

Read “First Breeding Confirmation of Swainson’s Warbler in Pennsylvania” in a 2023 PNHP newsletter.

Red-belted bumblebee

(Bombus rufocinctus)

The first red-belted bumblebee (Bombus rufocinctus) was found in Pennsylvania in 2017. While PNHP staff members were conducting bumble bee surveys in Great Lakes region, they discovered several red-belted bumblebees visiting coneflowers beside a road.

Red-belted bumblebees tend to prefer the flowers of clover, thistle, bonesets, goldenrods and asters in meadows, roadsides and other open areas. This bee is not currently listed as a SGCN. Our scientists are studying it for possible inclusion in the next SWAP.

Tiger Beetles

PNHP biologists spent two years studying three of Pennsylvania’s 16 tiger beetle species, which are globally vulnerable and may be declining in PA: the northern barrens tiger beetle (Cicindela patruela), the Appalachian tiger beetle (Cicindela ancocisconensis) and the cobblestone tiger beetle (Cicindela marginipennis).

With large eyes and long legs, tiger beetles can spot their prey from a distance and swiftly chase it down. Predatory tiger beetles live in open areas with little vegetation – such as barrens, river islands scoured by floods and riverbank sands deposited by floods. Threats include dams in rivers that prevent flooding, and invasive plants.

Read “Globally Vulnerable Tiger Beetles of Pennsylvania” in the 2023 PNHP newsletter.

Tiger Beetles

PNHP biologists spent two years studying three of Pennsylvania’s 16 tiger beetle species, which are globally vulnerable and may be declining in PA: the northern barrens tiger beetle (Cicindela patruela), the Appalachian tiger beetle (Cicindela ancocisconensis) and the cobblestone tiger beetle (Cicindela marginipennis).

With large eyes and long legs, tiger beetles can spot their prey from a distance and swiftly chase it down. Predatory tiger beetles live in open areas with little vegetation – such as barrens, river islands scoured by floods and riverbank sands deposited by floods. Threats include dams in rivers that prevent flooding, and invasive plants.

Read “Globally Vulnerable Tiger Beetles of Pennsylvania” in the 2023 PNHP newsletter.

Black-waved Flannel Moth

(Megalopyge crispata)

A newcomer to Pennsylvania, the Black-waved Flannel Moth (Megalopyge crispata) moved in from the south during the last couple decades. Not found in the 1990s barrens studies, it now common at WPC’s Sideling Hill Shale Barrens, and has been found at many sites in south-central PA.

In 2015 it was ranked it as S3, or vulnerable due to a restricted range, relatively few populations or recent and widespread declines, or other factors. However, it may be continuing to expand its range in PA, so it is important for PNHP biologists to re-assess the species for the 2025-2035 SWAP with new information about its distribution.

Wiggins’ Autumn Mottled Sedge

(Neophylax wigginsi)

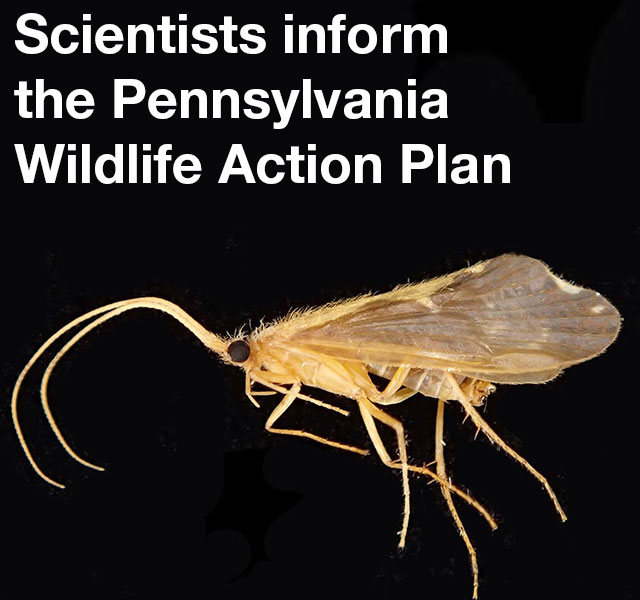

A caddisfly that was first described in 1978 from Pennsylvania specimens, Wiggins’ Autumn Mottled Sedge (Neophylax wigginsi) has since been found at other sites in the Appalachian Mountains, and it is considered globally vulnerable. WPC’s PNHP biologists have found this caddisfly at several sites in recent years, and suspect it is more common than the data indicate. It has not often been targeted with surveys.

The Wiggins’ Autumn Mottled Sedge will be evaluated for the next SWAP.

Wiggins’ Autumn Mottled Sedge

(Neophylax wigginsi)

A caddisfly that was first described in 1978 from Pennsylvania specimens, Wiggins’ Autumn Mottled Sedge (Neophylax wigginsi) has since been found at other sites in the Appalachian Mountains, and it is considered globally vulnerable. WPC’s PNHP biologists have found this caddisfly at several sites in recent years, and suspect it is more common than the data indicate. It has not often been targeted with surveys.

The Wiggins’ Autumn Mottled Sedge will be evaluated for the next SWAP.

Least Weasel

(Mustela nivalis)

The Least Weasel (Mustela nivalis) is the world’s smallest carnivore! It weighs about two ounces and is about eight inches long. It inhabits meadows, fields, brushy land and forests, mostly in the western third of the state, but during the past 20 years it has been sighted only a handful of times. Although considered nuisance animals by some, weasels help control other species populations and disperse seeds throughout the forest. Scientists want to learn more about the habitat and distribution of this species and two other species of weasels (long-tailed weasel and American ermine) in our state.

Our PNHP scientists and the PA Game Commission have set up game cameras to detect least weasels and determine which microhabitats to target when surveying for this elusive species. The results will help inform a conservation status assessment of Pennsylvania’s least weasel population.

Read “Weasels of Pennsylvania” in a 2023 PNHP newsletter.

Green Salamander

(Aneides aeneus)

In 2023, PNHP zoologists observed four Green Salamanders (Aneides aeneus) climbing on one red oak tree — the first documented successful targeted nighttime survey of trees for the state-threated species. Data from a resultant grant-funded study will inform landowners and land managers about occupied habitat use, appropriate forestry buffers and forest age preferences. With its small, flat body, prehensile tail and square toe tips, it is adapted for climbing in its very specific preferred habitat: moist, shaded rock crevices. Learn about the PFBC Green Salamander Species Action Plan.

Read “Green Salamander” in a 2022 PNHP newsletter.

Green Salamander

(Aneides aeneus)

In 2023, PNHP zoologists observed four Green Salamanders (Aneides aeneus) climbing on one red oak tree — the first documented successful targeted nighttime survey of trees for the state-threated species. Data from a resultant grant-funded study will inform landowners and land managers about occupied habitat use, appropriate forestry buffers and forest age preferences. With its small, flat body, prehensile tail and square toe tips, it is adapted for climbing in its very specific preferred habitat: moist, shaded rock crevices. Learn about the PFBC Green Salamander Species Action Plan.

Read “Green Salamander” in a 2022 PNHP newsletter.

Devil Crayfish

(Lacunicambarus diogenes)

PNHP scientists surveyed 94 sites within the potential range of the devil crayfish (Lacunicambarus diogenes) in southeastern Pennsylvania; this information will be applied to evaluation as an SCGN for next SWAP. This burrowing crayfish was found at one location only, suggesting it is one of the state’s rarest aquatic species Invasive red swamp crayfish (Procambarus clarkii) threaten to outcompete this native crayfish at its one known locale in Neshaminy State Park.

Devil crayfish is not currently listed as SGCN. Our scientists are studying it for possible inclusion in the next SWAP.

Wood Turtle

(Glyptemys insculpta)

Data suggests Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) populations are declining. PNHP and PFBC biologists, partners and volunteers conducted wood turtle population surveys at more than 74 stream locations during a two-year period. Data from these and earlier surveys will help determine the wood turtle’s conservation status.

Biologists are studying the turtles’ movements at priority sites. To improve habitat and promote nesting, they’ll remove invasive woody plants shading the turtles’ preferred nesting areas and possibly create sand mounds.

Wood Turtle

(Glyptemys insculpta)

Data suggests Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta) populations are declining. PNHP and PFBC biologists, partners and volunteers conducted wood turtle population surveys at more than 74 stream locations during a two-year period. Data from these and earlier surveys will help determine the wood turtle’s conservation status.

Biologists are studying the turtles’ movements at priority sites. To improve habitat and promote nesting, they’ll remove invasive woody plants shading the turtles’ preferred nesting areas and possibly create sand mounds.

Help Species of Greatest Conservation Need

- Use the PA WAP Conservation Opportunity Area Tool, which includes conservation actions.

- Check out PA WAP Chapter 4 “Take Action! Get Involved!”

- Use iNaturalist and iMapInvasives to help scientists track and monitor species.

- Protect habitat by conserving land or supporting land conservation efforts.

- Keep a smaller lawn and consider converting lawn to meadow. Watch “Plant It and They Will Come.”

- Keep a “messy lawn” to support fireflies and stem nesting bees.

- Get tips to control invasive species.

- Volunteer to control invasives on WPC preserves.

- Build bat boxes.

- Leave turtles, salamanders and other species in their natural habitats.

- Turn off lights at night to help night-flying insects and birds.

- Watch “Seven Simple Ways to Help Our Birds.”

- Donate to support conservation science and other work of WPC.