Conservation Science

Protecting Pennsylvania's Plants and Animals

Limestone Habitats

Pennsylvania is home to a great diversity of plant species. These plants have adapted over time to fill different ecological niches in the landscape. One way that they specialize is according to mineral availability. For example, the iconic rhododendron and mountain laurel of Pennsylvania’s mountain ridges are members of the heath family, most of which have specialized in acidic soils. They can absorb nutrients at low pH levels and are unperturbed by levels of free aluminum that would be toxic to other plants. Most of Pennsylvania is underlain by acidic bedrock, which is why these species are so ubiquitous. At the other end of the mineral spectrum are calcium-rich environments like limestone, which host their own specialist plants. Only 10% of Pennsylvania has calcium-rich bedrock, which is why a calcium-lover like wild columbine is not the state flower.

The small portion of the state with calcareous limestone bedrock makes an outsized contribution to its biodiversity. One-third of the state’s native vascular plants use calcareous habitats, and about 10% - almost 200 species - can grow nowhere else.

This abundance of plant species includes both wetland and upland plants, ranging from delicate ferns to dramatic orchids, and a whole host of lesser-known species as well. A Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program study has improved our understanding of which plant species depend on calcium-rich habitats and identified their conservation needs.

As part of this project, we identified plant communities that are found on calcareous soils.

- Sideoats grama grasslands are extremely unique because they host disjunct populations of prairie species, meaning they are separated from the main part of their range out west. Did you know that further west, soils tend to have higher pH because there is so little rain to leach away the minerals? These prairie species have found a pocket of home on droughty slopes in Pennsylvania’s limestone valleys.

- Rich fens are open, herbaceous communities that form in wetlands fed by calcium-rich groundwater. These communities host many northern species, where our Pennsylvania populations are near the southern edge of their global range.

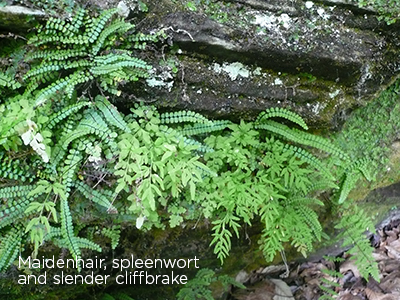

- Mesic outcrops of limestone or other calcium-rich rock host unique assemblages of plants, including the wild columbine and walking fern.

- Woodlands are found on steep slopes, often formed above rivers where the action of the water has exposed limestone bedrock over time. These dramatic-looking cliff communities host the highest diversity of calcium-loving plants among the terrestrial types.

These habitats are also important to many animals, especially butterflies and moth species that have calcium-loving host plant associations. PNHP continues to assess rare species such as the northern metalmark, which uses golden ragwort as a host plant, and Henry’s elfin, which uses the eastern redbud as a host plant.

Sideoats grama grassland communities in central Pennsylvania.

Rich fens are high in calcium, giving them specialized flora.

A lush and moss-covered mesic calcareous outcrop plant community.

Steep cliff with a calcareous woodland community.

Diversity Under Threat

Limestone habitats face many conservation challenges, and very little of this habitat remains in the state. Because these soils are “sweet” for agricultural crops as well, and tend to be located in prime areas for settlements (Pittsburgh, Altoona, Erie), natural vegetation has been cleared at a much higher rate than the state as a whole.

As a result, Pennsylvania’s remaining limestone habitats tend to exist in small patches that are often isolated from other natural landscapes. This poses serious threats to their long-term viability. Small patches are more vulnerable to invasion by non-native species, and lack of connection to other natural landscapes may cut off populations from access to pollinators, seed-dispersing animals and genetic exchange with other regional populations.

Many limestone habitats also depend on periodic disturbances, such as fire or grazing, to preserve their suitability for light-loving herbaceous species. Wildfires have been suppressed for the better part of a century in Pennsylvania, and low-intensity grazing has also declined with changing farm practices. As a result, many of these habitats are now closing in. Without active management to re-introduce similar disturbance effects, we will see a decline in diversity.

Already, nearly 60% of the approximately 200 limestone specialist plants are rare, threatened or endangered in Pennsylvania. Urgent conservation action is needed in the form of land protection, management to re-introduce disturbance and control invasive species, and restoration of contiguity between limestone habitats and surrounding natural landscapes.

PNHP has studied calcareous fens through a community classification project, A Study of Calcareous Fen Communities in Pennsylvania (1995), and through our recently completed peatlands inventory project. We are collaborating with the Pennsylvania Game Commission to provide scientific guidance for their stewardship efforts on fen sites they own. Several globally endangered plants live exclusively in calcareous habitats, and each of these now has a Plant Recovery Plan. PNHP is working with the Pennsylvania Plant Conservation Alliance to carry out stewardship that is guided by these plans. We are also writing a Habitat Recovery Plan for limestone barrens to guide future stewardship efforts of these important habitats.

Fen habitat managed by fire

A fen surrounded by development